Jibril Latif

Wokeism: Can We Laught About It?

Jibril Latif Browning

The word woke emerged out of the black American experience in the 1930s. For decades, it denoted staying vigilant about physical threats of violence to black people, and for a long time the word served a certain pragmatic intercommunal utility. Black people would tell each other, “Stay woke brother” to stay safe from police brutality and other threats. However, to define today’s cancel culture, we can say it is broadly the attempt to ostracize others for violating perceived social norms, and when someone criticizes wokeism and cancel culture, two terms that are associated, no one claims that they are being anti-black or racist.

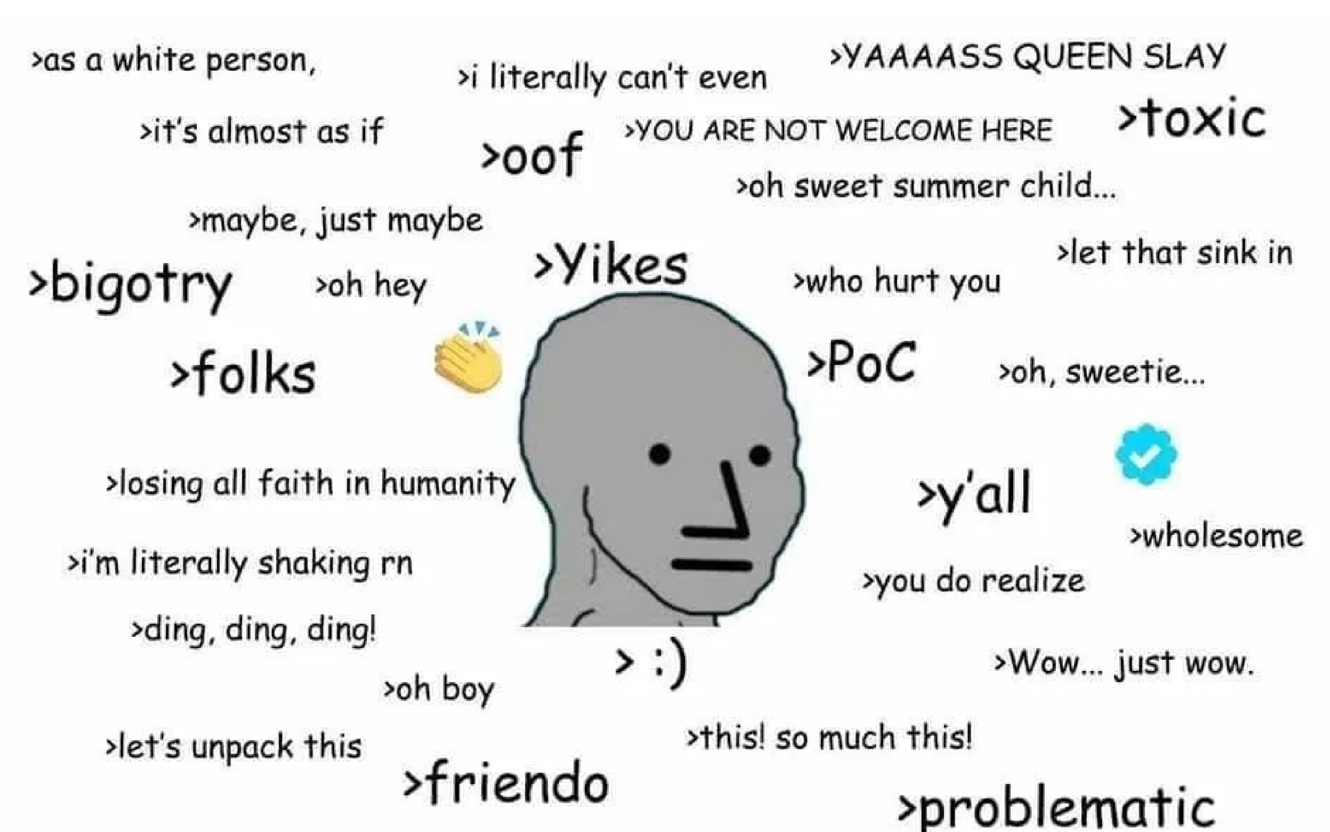

Therefore, one could argue that anglophones left of center have entirely expropriated the word woke from black Americans and integrated it into an ideological movement with roots in post-modernism, intersectional feminism, antiracism, and adjacent ideologies, and that terms developed by academics in these disciplines have been deployed journalistically against targets since 2012 in a pivot to prescriptivism that has coincided with the rise of Big Tech, the failure of legacy media business models, and a generation of narcissistic and coddled minds reaching adulthood. As these “woke” people have graduated and assumed positions of power in recent years, the institutions of previous repute now under their control have been visibly scrambling to adopt an almost slavish adherence to an ideological protocol with insatiable checklists: pronouns in bios, diversity quotas, equity statements, and land acknowledgment statements. While these signify virtue to some, they signify repression for others.

One could even say that to the varying degrees that woke ideology has become hegemonic in its permeation of academic institutions, media, and corporate culture, a spiral of silence represses a silent dissenting majority. However, there are people who push back and challenge political correctness, that are colloquially called “based” and “red-pilled” which are terms that have come to mean someone who is rational and or antihegemonic. The discernable phenomenon under investigation, therefore, is that the ones who seem able to survive cancellation often do so through the use and shield of comedy, and if and when they survive cancelation, they are thereby heroized for their authenticity and antisystemness, setting the foundations of a counter-hegemonic narrative and alternative media sphere.

David Chapelle Kevin Hart

The based hero par excellence is Dave Chappelle, who has achieved possession of a license for social critique unmatched by his peers for speaking to issues that touch on deeply held beliefs people feel afraid to voice. To a lesser extent, this helps to begin contextualizing the phenomenon of a large demographic of males, mostly younger but not exclusively, gravitating towards content from Jordan Peterson, Andrew Tate, and Joe Rogan which coincides with the increasing irrelevance that legacy media has on this demographic which has lost trust in journalism, mainstream news and institutions seen as woke.

This phenomenon also helps contextualize the arguments about Critical Race Theory in schools in the U.S., and why the American comedian Kevin Hart was cancelled and banned from performing his comedy set in Egypt for affirming “Afrocentrism”. These spectacles and debates often play out most visibly in what appear to be surface level disagreements about pronouns, race and gender, but in actuality they are deep philosophical disagreements about first principles, metaphysics, and beliefs about the nature of reality as long held norms and beliefs are being challenged.

Jibril Latif Browning Assistant Professor of Mass Communications and History of the Middle East at GUST.

Jibril Latif Browning Assistant Professor of Mass Communications and History of the Middle East at GUST.

Back to Meridian 4.png)