Mohammad Alwahaib

LEAD ARTICLE

One State or Two? An Exploration

of Hannah Arendt's Solution to the

Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

Mohammad Alwahaib

This article explores the horizons of two classical solutions to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, namely, the one-state and the two-state solution. Instead of focusing on the historical circumstances and events that lead to the emergence of these two solutions, I will try to focus on the advantages and disadvantages of both. The second part of this article is devoted to Hannah Arendt’s proposal to end the conflict, which is to be found in her early writings on the so-called Jewish question. This article will explore Arendt’s proposal in light of the present reality of the conflict.

Two broad solutions, interspersed with many details, are at the forefront of thinking today regarding a solution to the Palestinian question, despite the fact that one is more well-known than the other. The first solution, and probably the most famous one, is the two-state solution; the other is the one-state solution. The two-state solution implies the creation of two independent states, Palestine and Israel, given that each of the parties involved in this issue already wants to lead and govern their own state in a different way: the Israelis want a Jewish state while the Palestinians want a Palestinian state. Given the contradiction of these visions, the rational solution would be providing each of them an independent state. This solution has its roots in the United Nations resolution of 1947.

The "one-state" solution views the end of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict in the creation of a federal or Confederate state encompassing Israel's geographical territory, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and east Jerusalem. This solution necessarily involves Israelis losing their dream of a national state to Jews and Palestinians losing their dream of independence and national statehood.

The fact is that with the ongoing stubborn policies of the Israeli government and its refusal to demarcate its boundaries, talk of any form of peace seems impossible. While almost every reflection on the Palestinian question brings us back to these solutions, the real problem is that the reality of today forces us to realize how impractical they are. That these two solutions became alienated from reality, is probably predicted by Hannah Arendt in the 1940s. The prediction was proven to be true to a large extent: the partition of Palestine caused the destruction of the Arab-Palestinian entity, and the de-facto Israeli annexation of the West Bank has hindered and paralyzed the Palestinian Authority from acting as an independent sovereign state.

Today's reality is more complex than that experienced by Arendt. Israel never stopped seizing the territory of Palestine, and every time it does so, we find it disturbing that the world affirms Israel’s right to exist, while consciously and thoughtfully denying the Palestinians this right. The two traditional solutions have been reduced to one: one state, Israel, built entirely on the ruins of a destroyed Palestine. That has been the case in all its hideousness since 1948 until today, and if the situation continues at the current pace, Palestine will be erased from existence, and the Palestinians will become ‘homeless’ people, trapped in a geographical area with no identity – stateless, if you will, in a state that exercises its tyranny by rejecting their right to exist. This was actually announced by former United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process Robert H. Serry in 2012: after criticizing the construction of continuous settlements, Siri said, "we could be moving down the path toward a one -state reality.” [1]

A quick survey of the literature on the subject of the two-state solution reveals that when it is usually rejected, it is actually rejected for the following reasons:

1. The Zionists and most Israelis today have no doubt that what they really want is all of Palestine. All those flimsy arguments, which disrupt the negotiations and turn it into a "process", are only procrastinating to buy time without concrete action. The failure of the “peace process” is an obvious sign of that intention.

2. A two-state solution is a destructive solution for geography and human togetherness since it separates people and turns this small region into Swiss cheese.

3. The Palestinians will never give up the right to return for nearly one million refugees from diaspora, and Israel will not agree. The Israelis will never accept to be outnumbered by the Palestinians.

4. Muslims, Christians, Jews, or even seculars who are interested in any representation in any government will not give up on the idea of ruling over Jerusalem either partially or fully. Jerusalem will always be a central problem for all parties.

6. More than 400,000 Jewish settlers reside illegally in the occupied territories and refuse to leave their settlements at all costs. This could be one of the most important factors that would hinder the two-state solution.

7. Israel today looks like a military barracks with its military wing refusing to allow any form of sovereignty to the Palestinians as a neighboring country: the new emerging Palestine, if there is any, will not be allowed to have an airfield, or a special airport; it will not be able to create any military force that could pose a threat to Israel, have no water rights and no access to the sea at all costs.

8. Any order, any suggestion, to remove any settlement, whether it is legal or illegal, is met with great concern, anxiety, and probably distrust by Jews since it reminds them of the diaspora and the Holocaust. This also applies to all Jews all over the world.

9. The daily life situation in the Palestinian territories is very poor, harsh and very difficult—a situation that will probably lead to one intifada after another and further violence. These poor living conditions will always be understood from the Palestinian point of view as a result of the Israeli occupation. The two-state solution, then, is probably a fragile project, given the constant Palestinian threat.

Why Hannah Arendt’s proposal?

The frightening reality of a Palestinian state through a two-state solution might prompt us to think a little “outside the box”; and despite the difficulties facing the one-bi-national state project, I believe, it deserves some reconsideration. Today we are faced with a complex international reality, the signs of which are many:

1. The international community of today is unable to recognize or do anything about the destruction of Palestine, although the scene of the international order has begun to show some signs of change.

2. This conflict is a unique one: as the conflict between the Palestinians and the Israelis intensifies, both parties are aware implicitly that it is impossible for one of them to annihilate the other. Both parties know that eventually they must come up with an agreement.

3. The escalation in the last few years has led the majority of all parties to view violence as the only means, and unfortunately, the legitimate means of resolving the dispute. Violence, as we witnessed a few weeks ago, is something that might eventually lead to the destruction of all parties.

A few days ago, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas delivered the coup de grace to the moribund so-called peace process which began almost 30 years ago. This is an official de facto collapse of the negotiations between the Palestinians and the Israelis. At times like this, we will probably find an echo for Hannah Arendt’s call for a new discourse and a new solution, or in her own words: a new beginning. After 30 years of fruitless peace negotiations, many scholars have turned their attention to her early writings in the 1940s, and more specifically to her criticism of Zionism and its push towards the creation of a Jewish state.

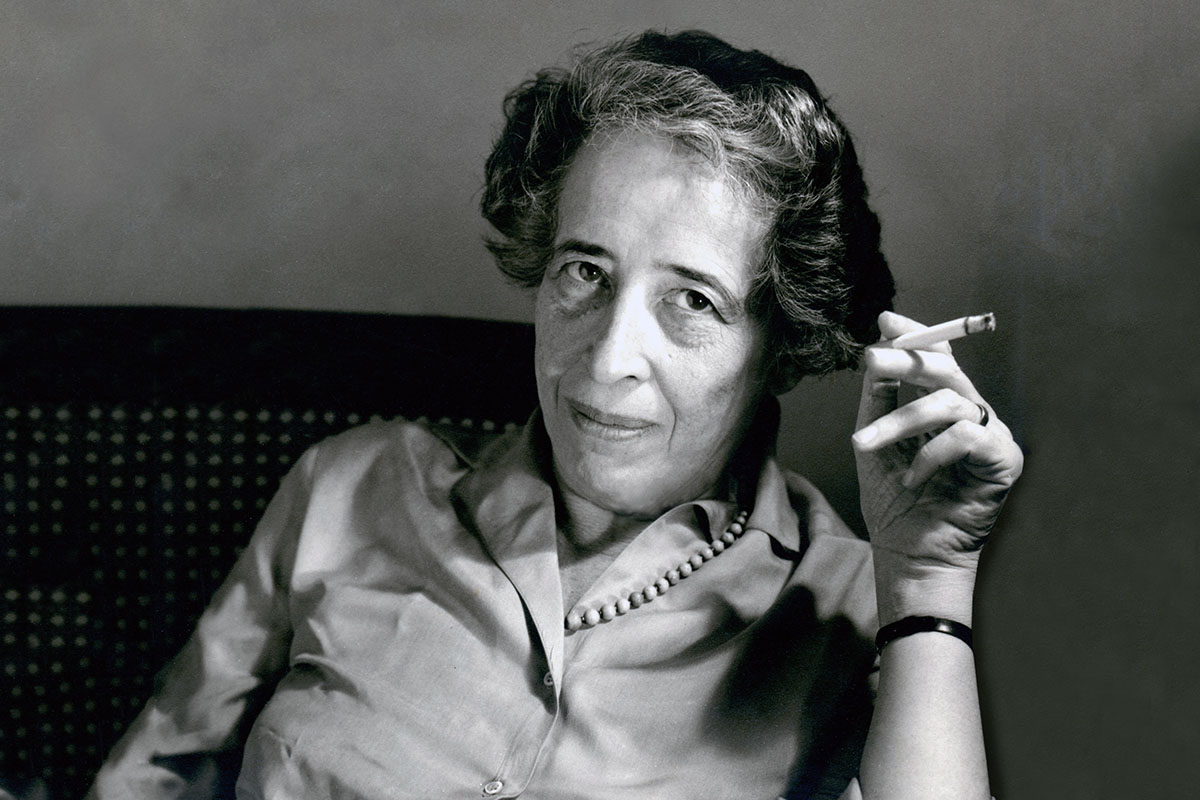

Hannah Arendt, for those who are unfamiliar with her biography, has traveled intellectually between many ‘islands’ of thought. She began her life with pure philosophical concerns, this is not surprising when we look at her academic background: in fact, she inherited the tradition of German philosophy through her education in German universities. She was a distinguished student and lover of Martin Heidegger in Marburg, and later in Heidelberg a pupil and a lifetime friend of Karl Jaspers. It is under the supervision of Jaspers that she wrote her first doctoral dissertation, the Concept of Love in St. Augustine. For most of the time she spent in universities, Arendt did not show any interest in political matters. However, when the Nazis rose to power in Germany, Arendt tells us, it was the occasion that made it possible for her to face the fact of her ‘Jewishness’—the vehicle that escorted her into politics. The hostility of the Nazis towards Jews, as well as other minorities, turned Arendt’s attention towards politics and ‘action’. Later, she was intensely engaged in Jewish politics and Zionism as an active passionate member. In the middle of all these events, Arendt declared her divorce from all forms of traditional philosophizing: “I left Germany [escaping from the Nazis] dominated by the idea… Never again! I shall never again get involved in any kind of intellectual business. I want nothing to do with that lot. [2]” This period of time that she spent involved in Jewish politics is marked by a number of articles on the so-called Jewish question and parts of her famous work, The Origins of Totalitarianism, and in these articles, we find an explicit, harsh [word missing] of the Zionist ideology.

These early writings on the Jewish question and Zionism, which began in 1937 and lasted for almost a decade, are the focus of this article. Arendt’s critique of Zionist ideology took three directions: first, the Zionist vision of the meaning or essence of the term, "Jewish people". Second, her analysis of the actual presence of Arabs in the territory of Palestine, and third, the absence of a Jewish policy independent of the world's great powers. I will try to look in some detail at the first and second critiques as they pertain more to our subject matter.

With regard to the Zionist vision of the meaning and the future of the Jewish people, Arendt criticized the Zionist concept of the nation-state and viewed it as a terrible and outdated form of a state. In fact, she labelled those who embraced this idea “the new fascists”, referring to those who commit themselves to the creation of a Jewish/ethnic national state. Against this national vision, Arendt proposed the establishment of an Arab-Jewish Confederation in Palestine, based on recognition of the plurality of individuals, and the guarantee of their equal rights.

Thinking of a "Jewish state" from a Zionist perspective was, for Arendt, a wrong reaction to anti-Semitism in Europe, since such a Jewish state will exercise the same hostility that Jewish people suffered but against the Arabs this time. Arendt recognized that such a state can only be established through force, and rightly so, since no people can accept the stealing of their land, or become stateless overnight, or at best, second-class citizens. Imposing a Jewish nation-state in that way would only lead to continued violence. Arendt predicted that even if the Jews won the war, they would:

"degenerate into one of those small warrior tribes about whose possibilities and importance history has amply informed us since the days of Sparta... Thus, it becomes plain that at this moment and under present circumstances a Jewish state can only be erected at the price of the Jewish homeland." [3]

You don't need to do much to persuade yourself of the reality of Arendt's predictions; all you need to do is walk down any street of Israel and see for yourself the heavily armed soldiers everywhere.

Arendt stood firm in the face of Zionist claims calling for the establishment of a Jewish state on the territory of Palestine, and because of the denial of the rights of those indigenous people she called for a bi-national state. The idea of a bi-national state is not new, of course, as it was preceded by some Jewish intellectuals such as Judha Leon Magnes, Gershom Scholem, Martin Buber and others, in addition to some associations such as Bret Shalom. This idea, bi-nationalism, meant for Arendt that the state should be separated from religion and national identity.

Youssef Munayyer wrote in the New Yorker, influenced by that Arendtian line of thought and in favor of a one-state solution:

"The reality now is that there is a single state. The problem is that it takes an apartheid form. Billions upon billions of dollars continue to be poured into the Israeli settlement enterprise. Natural resources are being exploited illegally. More and more land is being taken from Palestinians. Israeli infrastructure plans are growing. Everything about the Israeli state’s actual behavior suggests it has no intention of ever leaving the West Bank." [4]

Since the two-state solution is obsolete, Munayyer suggests that we should come to a practical, pragmatic recognition that we have in fact is a “one-state problem”, and that this recognition is “the key to peace”—all we need in this case is a regime change. Following the Arendtian spirit, he asserts that the first step in this change is ending legal discrimination based on ethnicity or religion throughout the entirety of the territory. Palestinians must be part and parcel of shaping any future state they will live in, and they can do so only on equal footing with their Jewish counterparts before the law, not under military occupation.

There is a problem concerning the difficulty of imagining this one bi-national state solution. The main reason behind this is the fact that the recent Palestinian and Israeli rhetoric has reached such a level of contradiction that it became so hard to speak of reconciliation or compromise. This is probably a logical conclusion to the Zionist premises: the Zionists were blinded to other partners on the same land and never considered them to be equal to them. Arendt explained this through historical events: the first Zionist program in 1942, issued in Biltmore, called for the establishment of a Jewish commonwealth in Palestine, and the Atlantic City program that followed, referred to a free Jewish Commonwealth covering the entire territory of Palestine without division. In the first program, minority rights were given to the Arab majority; in the second program, Arabs were never mentioned at all! This disregard for the Palestinians, she believed, is due to the increasing ideological tone of Zionism which goes hand in hand with its detachment from commonsense and reality.

But the problem seems to be deeper than just Palestinian and Zionist claims; the problem is one of land in which each of the parties to the conflict claims its right to it. We know well that one of the parties had lost the war, but the conflict did not end until today. The truth is that, after nearly seventy years of conflict, this land or the independent state of Jews has not been fully independent, and it still finds itself day after day trapped in the net of non-Jews. The problem of land is linked to a more complex problem of identity: Palestinians want to retain their Arab identity at all costs, given the Arab-Muslim region as part of which they want to see themselves, and Jews who want a Jewish state as envisioned in the Zionist ideology.

The central question for Arendt, I believe, as an alternative to the two-state solution, is the need to think along the lines of a bi-national state, to think of the possibility of peaceful coexistence between Jews and Arabs in a partnership that is based on equal rights. I believe that she really wanted to present a challenging alternative to us, an alternative that is based on the impossibility of getting rid of the other, one that looks at democratic institution-building, transitional justice and a new constitution. The fact of not being able to get rid of the other is, by the way, becoming an increasing conviction among Palestinians and Israelis day after day.

Expert on Jewish History at the University of Ben-Gurion, Amnon Raz Krakotzkin, may rightly believe that this Arendtian vision is one "with a temporal specificity that does not make sense outside the framework of that history." In his view, the one-state solution of Arendt is "a dreamy idea that does not reflect reality... Not more than a cultural contribution." [5] However, I believe that Krakotzkin’s conclusions are a bit hasty, in fact there seems to be a lot of factors to be considered before coming up with such conclusions. First, there are many Israeli and Arab intellectuals and activists today who resent the strong influence of some Orthodox, radical parties in Israeli and Arab politics, and this belief has pushed them to gather around the idea of a truly secular Israeli society in which citizenship rights are given to all.

Second, there are many Jewish Israelis who speak and write about the importance of entering the phase of "post-Zionism"; after nearly 70 years of Israeli history, traditional Zionism has provided neither a solution to Palestinians nor an independent Israeli existence.

Echoing the Arendtian spirit, Edward Said writes:

"I see no other way than to begin now to speak about sharing the land that has thrust us together, sharing it in a truly democratic way, with equal rights for each citizen. There can be no reconciliation unless both peoples, two communities of suffering, resolve that their existence is a secular fact, and that it has to be dealt with as such.” [6]

The alternatives are unpleasantly simple: either the war continues or a way out, based on peace and equality, as in South Africa after apartheid, is actively sought, despite the many obstacles. Once we grant that Palestinians and Israelis are there to stay, then the decent conclusion has to be the need for peaceful coexistence and genuine reconciliation.

Mohammed Alwahaib is the Chair of the Philosophy Department of Kuwait University

Mohammed Alwahaib is the Chair of the Philosophy Department of Kuwait University

Notes

1. https://dppa.un.org/en/security-council-briefing-situation-middle-east-special-coordinator-middle-east-peace-process-0

2. http://www.arendtcenter.it/en/tag/gunter-gaus/

3. Arendt, Hannah, To Save the Jewish Homeland: There is Still Time, Commentary Magazine, May 1948

4. Munayye, Yousef, Thinking Outside the Two-State Box, The New Yorker, September 20, 2013,

5. Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin, Jewish Peoplehood, "Jewish Politics," and Political Responsibility: Arendt on Zionism and Partitions, College Literature, Vol. 38, No. 1, Arendt, Politics, and Culture (Winter 2011), p. 62. Published By: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

6. Said, Edward, The One-State Solution, The New York Times Magazine, Jan. 10, 1999.

Back to Meridian 3